|

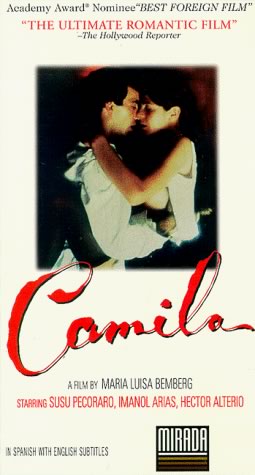

Película "Camila"

Directed by MARÍA LUISA BEMBERG

Argentina, 1984

Sinopsis:

"Camila" is a film based on real events. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. "Camila"

transcends the melodrama of tragic love by exploring the themes of political and religious freedom.

The story is set in the mid 1800's, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, during the dictatorship of Juan Manuel de Rosas, Argentina's

bloodiest and most violent regime. Camila O'Gorman is an aristocratic young woman who falls in love with Ladislao Gutierrez,

a young Jesuit priest. Though tormented by the forbidden nature of their love, Ladislao renounces the priesthood and escapes

with Camilia to the provinces, where they assume new identities and live as husband and wife. Their love affair becomes a

pawn in the Church's alliance with the aristocracy and the military dictatorship. When Ladislao is eventually recognized by

a fellow priest, he and Camila are arrested. The punishment they face for their crime is as bloody, cruel, and violent as

the regime of the man who ultimately condemns them: Juan Manuel de Rosas, for whom, "the true crime of Gutiérrez and

Camila was to have mocked his authority, and to have appeared to defy him in the eyes of society."

****************************************************

Film Review by Erik Cooke (March 23, 2005)

Today, when we picture a young, vivacious woman falling in love with and marrying the man of her dreams, we have visions

of weddings and bridal showers. In our day, we hardly think twice about former relationship taboos such as interracial marriage,

same-sex couples, or even older women marrying much younger men. It may even be a struggle to notice a young woman and a priest

falling in love and running away together. However, in 1840s Argentina, such a situation threatened to topple the authoritarian

regime of that country's leader. When Camila O'Gorman fell in love with a young provincial priest, Ladislao Gutierrez, sparks

flew.

Why was a budding romance such a menace to the authoritarian rule of Argentina's leader, Juan Manuel de Rosas? In the

eyes of the Rosas regime Camila O'Gorman committed a crime. In actuality, Camila threatened the male power structure that

existed in Argentina, which was enforced by the Catholic Church, Rosas, and her father, Adolfo O'Gorman. She embodied the

underlying tension inherent in gender relations of the day. It is necessary to examine the political and historical climate,

the social norms of the day, and the personality of Camila O'Gorman in this tragic tale to understand the reasons behind her

demise.

Bemberg depicts Camila as a young, free-spirited woman. Although raised in a Federalist household, she is largely unconstrained

by the conventions of her domineering father and of the repressive political climate of the day. Against the social grain,

she falls in love with a young priest and together they flee to live a life free of the dominance of Rosas and his rigid social

code.

What was Camila's crime? Ostensibly, she defiled a priest by taking him away from the church and engaging him in an adulterous

relationship. Her relationship threatened the sanctity and moral authority of the church. The Federalists, whom Rosas identified

with, were very close to the church. In fact, the Catholic Church in Argentina supported Rosas to such an extent that his

likeness was visible in many church buildings. In contrast, the opposition Unitarians, whom Camila identified with, opposed

the Catholic Church vigorously. In the eyes of the church, if Camila went unpunished, then others might have liberty to disregard

the church's laws and authority.

The fact that Camila's actions were labeled as a crime was primarily cover for the menace that she posed to Rosas' political

power by undermining his authority so boldly. It was exacerbated by growing Unitarian criticism from Chile and Uruguay to

his governance. Although it may not have been the public rationale for her crime, Rosas was loathe to allow such a bold and

well-publicized, independent spirit to subvert his authority. He was the final arbiter of justice and policy, and to underscore

his might, he chose to punish Camila and Ladislao for their crime by execution.

Although women were not usually put to death for such crimes, Rosas viewed Camila as a serious counter to his vision and

rule of Argentina. As a totalitarian, he quashed her "revolt" before she could incite other young minds to take

similar, or even more extreme, paths. He not only upheld the sanctity of the church, but also reestablished, rather loudly,

that he was the power in this nation. It was as much a signal to the populace as the meting out of justice.

Camila obviously had the ability to undermine Rosas' power to some degree. However, it was not simply the dictator's political

authority or the Church's moral authority that she menaced with her independent spirit. Her father was troubled by the fact

that she was unmarried, and determined that she needed to marry or join a convent. There was no option. In his mind, women

had only these two choices. Because Camila flouted her father's wishes by remaining so unencumbered, she subverted not only

his wishes, but his familial authority as well.

Not only did his daughter vex Adolfo O'Gorman personally, but also as a loyal supporter of the country's leader, Rosas,

he needed to align himself with the rigid position of the state. This same man is presented in the beginning of the film as

having exiled his own mother for an adulterous affair with the Viceroy Liniers. If he was to be seen by the state and his

contemporaries as fair and loyal, he must proceed no differently with his daughter.

It becomes obvious, then, that Camila presented the same problem to many levels of the male authority figures in her country.

In order to maintain the social order, each felt the need to assert their dominance and to control her. By keeping an iron

fist on Camila, Argentina's male authority system - whether on the political, moral, or familial level - maintained control

over all females in Argentina. Because she threatened such a wide swath of the power structure, her punishment was dealt to

her so severely.

Other films by María Luisa Bemberg:

De eso no se habla (1993)

Yo, la peor de todas (1990)

Miss Mary (1986)

Camila (1984)

Señora de nadie (1982)

Momentos (1980)

Read an essay on Argentina's history and Rosas' regime

Handout: questions on the film

|